The Planets

Besides the sun, moon, and stars, there are five other prominent objects

in the sky: the planets Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Their complex motions mystified

ancient people, and eventually motivated the development of modern astronomy.

Appearance

To the naked eye, each of these five planets looks like a bright

star. Venus is the brightest, brighter than any star and sometimes visible in the

daytime (if you know where to look). Jupiter is also brighter than any star, while Mars

is quite variable, sometimes as bright as Jupiter and sometimes only a little brighter

than the North Star. Mercury and Saturn are never as bright as Jupiter, but

are still brighter than all but a few of the stars.

Exercise: Use the

Sky Motion Applet

to determine which planets are currently visible in the night sky, and at what times, and

in which directions.

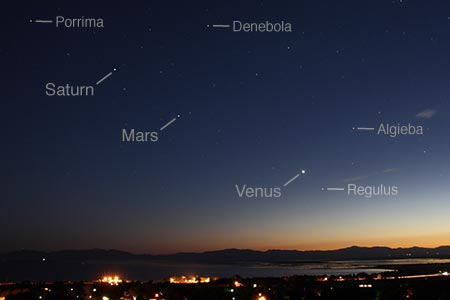

Question: The photo above was taken on a July 2010 evening from northern

Utah. Use this information and the

Sky Motion Applet

to reproduce this configuration of

the planets with respect to the surrounding stars. On what date in July was the photo taken?

Motion

Although the planets look like stars, their motions through our sky

are much more complicated.

On any given day/night, they rise and set like a star would. But like

the sun and moon, they gradually wander among the twelve constellations of the zodiac,

always staying close to the ecliptic.

In fact, the word "planet" comes from the Greek word for "wanderer", and in this sense,

the sun and moon were also originally classified as planets. One vestige of this old

classification is our names for the days of the week, one for each of the seven

original "planets" (see table at right). Nevertheless, to avoid confusion, I'll use

the word planet (in this chapter) to refer only to the five star-like wanderers, not

including the sun and moon.

Besides their star-like appearance, the planets differ from the sun and moon in the

details of their motions. Recall that the sun and moon both move along (or near) the

ecliptic from west to east—that is, leftward if you're at a northern latitude,

looking up into the southern sky. The five planets also move from west to east most

of the time, but not always. Instead, they periodically slow down (with respect to the

stars), stop, and reverse direction, moving from east to west. Then, after a few weeks or

months,

they reverse direction again, resuming the usual eastward motion. The more common eastward

motion is traditionally called forward motion, while the less common westward

motion is called retrograde motion.

Retrograde motion is easy to observe, as long as you're somewhat familiar with the

constellations and have enough patience to make observations over several nights.

The retrograde motions of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn conveniently occur when they are

opposite the sun in our sky, and hence visible all night long; we then say that they're

at opposition. These planets are also

at their brightest when at opposition, though the brightness differences aren't nearly

as great for Jupiter and Saturn as they are for Mars. The time interval between one

opposition and the next is about 780 days for Mars, 399 days for

Jupiter, and 378 days for Saturn.

Venus and Mercury, on the other hand, are never opposite the sun in our sky. Instead

they stay relatively close to the sun: Venus within about 47 degrees and Mercury within

about 28 degrees. This means that these planets can be visible either in the western sky after

sunset, or in the eastern sky before sunrise, but never near midnight.

Mercury, in particular, is hard to observe over long periods because it is always

so close to the sun.

Retrograde motion, for either Mercury or Venus, occurs when the planet has been visible in our

evening sky, then quickly approaches the sun (from our perspective) and later appears on its

other side, in our morning sky. The planet's forward motion then gradually carries it back

toward the sun from the other side, and eventually back into our evening sky.

This pattern repeats about every 584 days for Venus and every 116 days

for Mercury.

To help you visualize these motions, I've created a

Whole Sky Applet

that draws the planets on a map of the entire (360-degree) sky. Please spend some time

playing with this applet, watching the forward and retrograde motions of each of the

five planets. Then use this applet (or the

Sky Motion Applet) to answer

the following questions.

Question:

Observe the forward and retrograde motions of Jupiter. About how long does each period of retrograde

motion last?

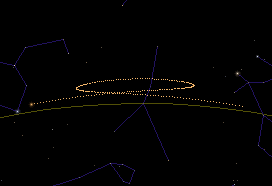

Question:

As shown above, Mars was in the constellation Cancer during its retrograde motion in late 2009 and early 2010.

Which constellation will Mars be in during most of its next retrograde motion, in early 2012?

The intricate motions of the planets were a wonder and a mystery to ancient people who

took the time to observe and ponder them. It was natural that most ancient people considered

the erratically moving planets to be deities, with wills of their own.

It was also natural for people to conjecture

that, like the sun and the moon, the planets might have noticeable effects on our daily lives

here on earth. This idea was developed into astrology,

a subject that gets far more attention than astronomy even in today's newspapers and bookstores.

Meanwhile, the

ancient Greeks eventually attempted to devise mechanical models to explain (and predict)

the complex motions of the planets. These efforts are described in the following chapter.

Copyright ©2010-2011 Daniel V. Schroeder.

Some rights reserved.